Is immigration good or bad? Some argue that immigrants flood across borders, steal jobs, are a burden on taxpayers and threaten indigenous culture. Others say the opposite: that immigration boosts economic growth, meets skill shortages, and helps create a more dynamic society.

Evidence clearly shows that immigrants provide significant economic benefits. However, there are local and short-term economic and social costs. As with debates on trade, where protectionist instincts tend to overwhelm the longer term need for more open societies, the core role that immigrants play in economic development is often overwhelmed by defensive measures to keep immigrants out. A solution needs to be found through policies that allow the benefits to compensate for the losses.

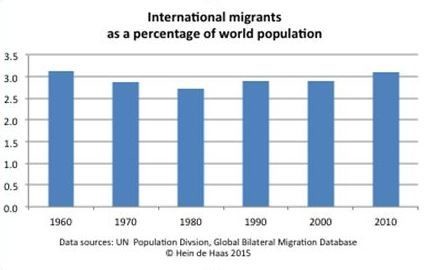

Around the world, there are an estimated 230 million migrants, making up about 3% of the global population. This share has not changed much in the past 100 years. But as the world’s population has quadrupled, so too has the number of migrants. And since the early 1900s, the number of countries has increased from 50 to over 200. More borders mean more migrants.

Of the global annual flow of around 15 million migrants, most fit into one of four categories: economic (6 million), student (4 million), family (2 million), and refugee/asylum (3 million). There are about 20 million officially recognized refugees worldwide, with 86% of them hosted by neighbouring countries, up from 70% 10 years ago.

In the US, over a third of documented immigrants are skilled. Similar trends exist in Europe. These percentages reflect the needs of those economies. Governments that are more open to immigration assist their country’s businesses, which become more agile, adaptive and profitable in the war for talent. Governments in turn receive more revenue and citizens thrive on the dynamism that highly-skilled migrants bring.

Yet it is not only higher-skilled migrants who are vital. In the USA and elsewhere, unskilled immigrants are an essential part of the construction, agriculture and services sector.

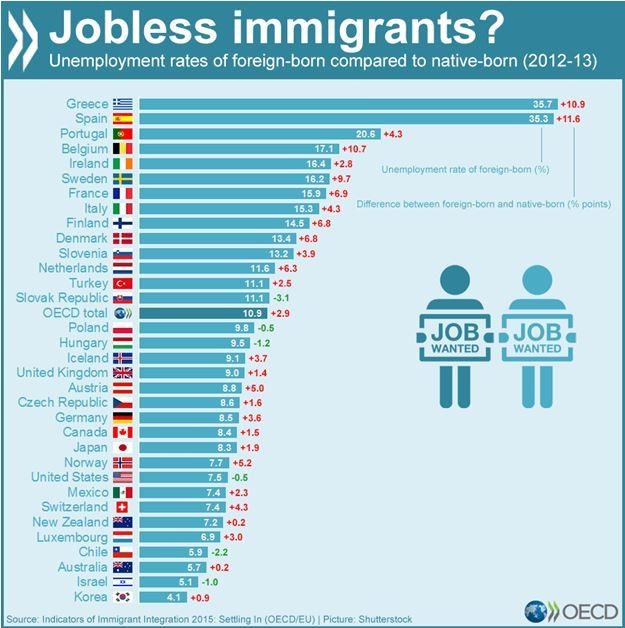

If immigrants play such a vital role, why is there so much concern?

Some believe that immigrants take jobs and destroy economies. Evidence proves this wrong. In the United States, immigrants have been founders of companies such as Google, Intel, PayPal, eBay, and Yahoo! In fact, skilled immigrants account for over half of Silicon Valley start-ups and over half of patents, even though they make up less than 15% of the population. There have been three times as many immigrant Nobel Laureates, National Academy of Science members, and Academy Award film directors than the immigrant share of the population would predict. Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco concluded that “immigrants expand the economy’s productive capacity by stimulating investment and promoting specialization, which produces efficiency gains and boosts income per worker”.

Research on the net fiscal impact of immigration shows that immigrants contribute significantly more in taxes than the benefits and services they receive in return. According to the World Bank, increasing immigration by a margin equal to 3% of the workforce in developed countries would generate global economic gains of $356 billion. Some economists predict that if borders were completely open and workers were allowed to go where they pleased, it would produce gains as high as $39 trillion for the world economy over 25 years.

In the future, it will become even more imperative to ensure a strong labour supply augmented by foreign workers. Globally, the population is ageing. There were only 14 million people over the age of 80 living in 1950. There are well over 100 million today and current projections indicate there will be nearly 400 million people over 80 by 2050. With fertility collapsing to below replacement levels in all regions except Africa, experts are predicting rapidly rising dependency ratios and a decline in the OECD workforce from around 800 million to close to 600 million by 2050. The problem is particularly acute in North America, Europe and Japan.

There are, however, legitimate concerns about large-scale migration. The possibility of social dislocation is real. Just like globalization – a strong force for good in the world – the positive aspects are diffuse and often intangible, while the negative aspects bite hard for a small group of people.

Yes, those negative aspects must be managed. But that management must come with the recognition that migration has always been one of the most important drivers of human progress and dynamism. Immigration is good. And in the age of globalization, barriers to migration pose a threat to economic growth and sustainability. Free migration, like totally free trade, remains a utopian prospect, even though within regions (such as Europe) this has proved workable.

As John Stuart Mill forcefully argued, we need to ensure that the local and short-term social costs of immigration do not detract from their role “as one of the primary sources of progress”.

Author: Ian Goldin is Director of the Oxford Martin School and Professor of Globalization and Development at the University of Oxford. This article draws on his book Exceptional people: How migration shaped our world and will define our future, co-authored with Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan and published by Princeton University Press. Twitter: @oxmartinschool. He is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Author: Ian Goldin, Professor of Globalization and Development, University of Oxford. Ian Goldin is Director of the Oxford Martin School, Professor of Globalization and Development at the University of Oxford, and Vice-Chair of the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations.

source: WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM